Yesterday evening I visited Our Lady’s Hall to see the plans for the new library in Drimnagh. The architect was there to talk me through them – they look great!

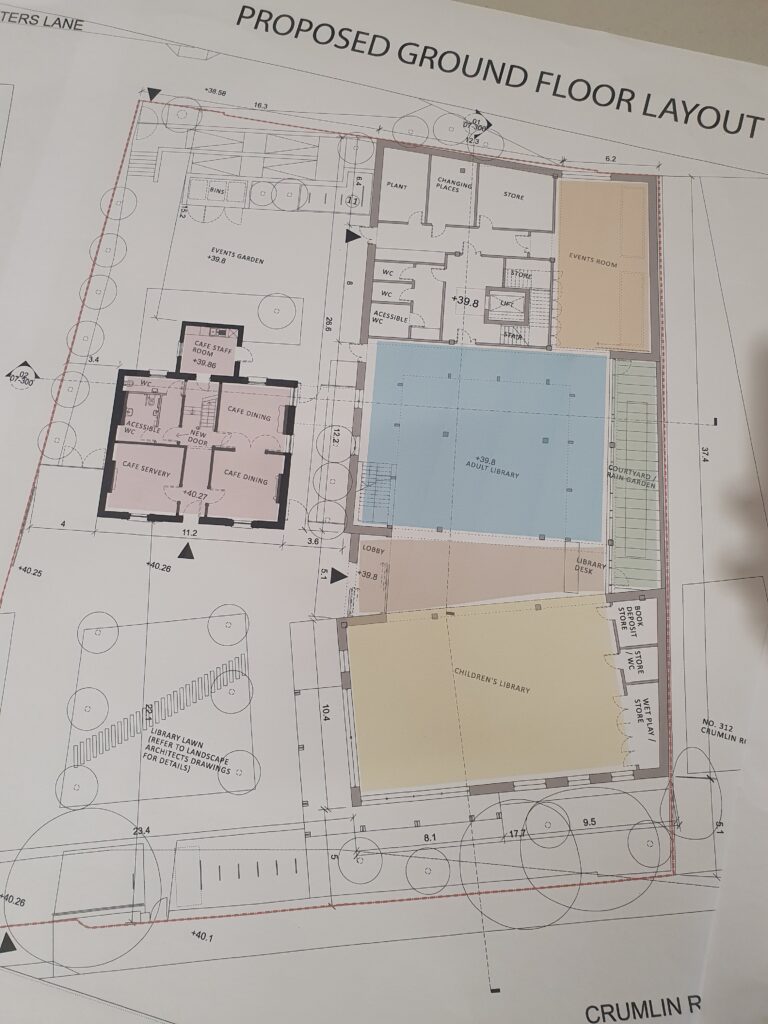

The library will be built on the site of the old Ardscoil Eanna, Franshaw House. The house itself will be restored, and a cafe opened on the ground floor. The space in front of and behind Franshaw House will be gardens. (The west of the site, towards Rafters Road, is earmarked for housing, but the plans are not ready yet)

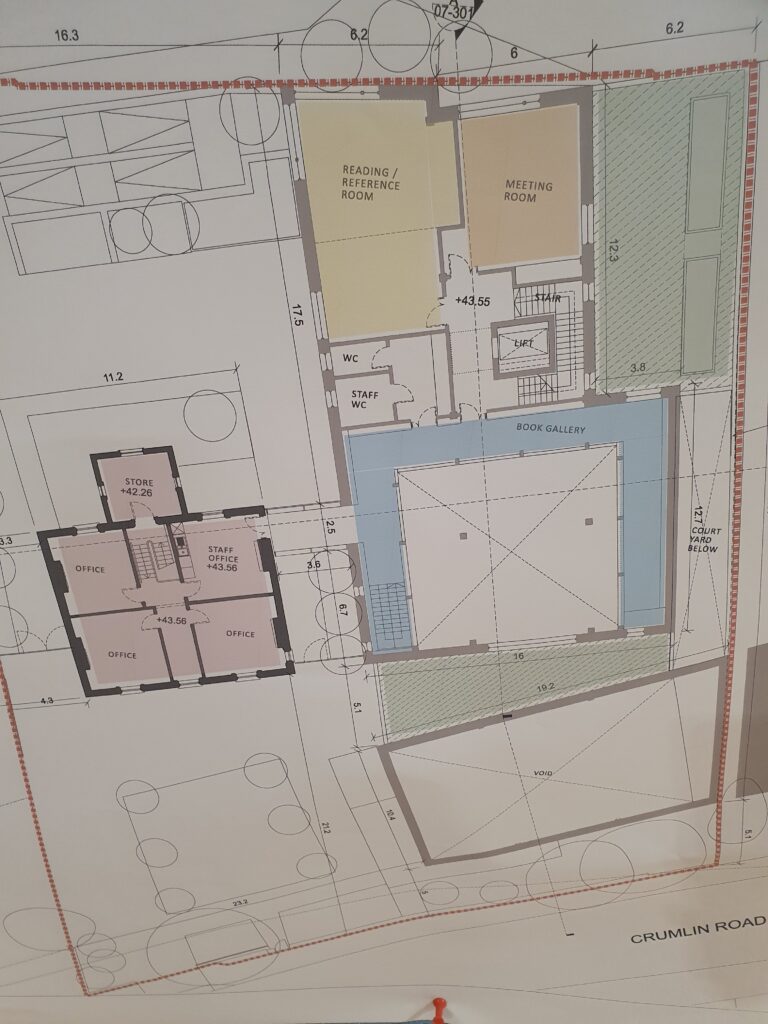

The library will have large children’s and adult sections – a double-height room for the children, a book gallery above for the adults. There is also an events room, a meeting room, and a conference room.

The site gets lower from Crumlin Road to Rafters Lane, so there are ramps at the Rafters Lane entrance for wheelchair/buggy access. Franshaw House itself was not designed for accessibility, and there is no space for a lift, so the first floor of the library will connect to the first floor of the house, making all areas accessible.

So when will it open? The project is going for planning permission in the next few weeks, with the expectation that permission will be granted in the autumn. At that stage, more design work has to be done on the interiors. The council could tender for people to do the work early next year, and then roughly another year to get it built. So it will most likely be early 2026. The good news is that the money has already been set aside by the council, there should be no delays there.

I live just around the corner from Walkinstown library, and it is a great community hub. It fills so many roles – parents bring their kids there, mother and toddler groups meet, school groups come in, students study, community groups hold meetings… it’s hard to overstate the importance of having a place you can spend time, without spending money, all through the day. And it’s full of books! This is going to be a great addition to Drimnagh, I can’t wait until it opens.